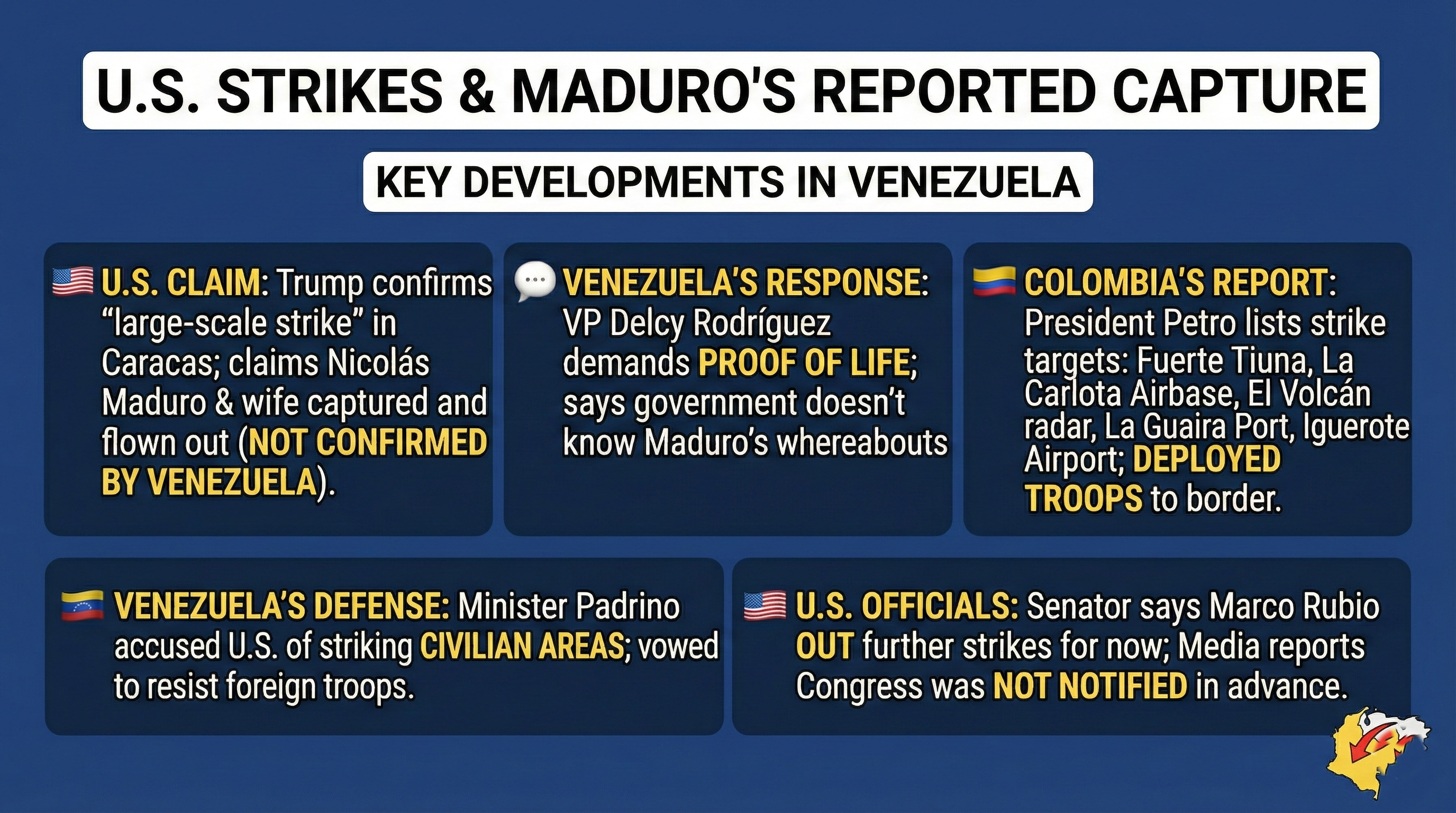

A time bound account of sanctions disputed elections counter narcotics justification. And the January 2026 US air strikes on Caracas. […]

Neural Circuits Underlying Guilt and Shame Regulated Human Behavior

Human societies depend on subtle emotional mechanisms that regulate behavior long before laws, institutions, or punishments come into play. Among these mechanisms, guilt and shame play a central role. They influence whether individuals attempt to repair harm, cooperate with others, withdraw from social contact, or engage in self-protective behaviors. Although these emotions are deeply familiar in everyday life, their cognitive origins and neural foundations have remained poorly understood.

A new study published in eLife by researchers from Sun Yat-sen University and Beijing Normal University provides compelling behavioral, computational, and neural evidence explaining how guilt and shame arise from distinct cognitive processes and how they guide compensatory actions. The findings shed light on how humans translate moral emotions into social behavior, with broad implications for psychology, neuroscience, psychiatry, and public policy.

Guilt and shame: Similar origins, divergent outcomes

Guilt and shame frequently co-occur after a person engages in behavior perceived as morally wrong. Both emotions serve an adaptive function by discouraging future violations of social norms. However, decades of psychological research have shown that guilt and shame differ in their emotional tone, mental health associations, and behavioral consequences.

Guilt is primarily action-focused. It is associated with remorse over having caused harm and is strongly linked to prosocial outcomes such as apologizing, compensating victims, and engaging in altruistic behavior. Importantly, guilt tends to be unrelated or even negatively related to anxiety, depression, and stress.

Shame, by contrast, is self-focused. It is associated with negative self-evaluation and heightened concern about how one is perceived by others. Psychologically, shame correlates strongly with anxiety, depression, and stress. Behaviorally, it is less likely to drive cooperative actions and more likely to produce avoidance, concealment, evasion, and sometimes antisocial responses.

Despite these well-documented differences, the cognitive triggers that give rise to guilt versus shame and the neural mechanisms through which these emotions translate into behavior have remained unclear. The new study directly addresses these gaps.

The unresolved question: What triggers guilt versus shame?

Previous research has identified two key factors that contribute to moral emotions:

Harm– the severity of damage or suffering caused to another person

Responsibility– the degree to which an individual perceives themselves as personally responsible for causing that harm

While both factors are known to influence guilt and shame, it has been unclear whether they exert equal or distinct effects on each emotion. It has also remained uncertain whether guilt- and shame-driven behaviors rely on the same or different neural circuits.

As first author Ruida Zhu explains, extensive studies have documented the psychological and neural correlates of guilt and shame, but their cognitive antecedents, the precise triggers that precede the emotional experience, have not been systematically disentangled.

A novel experimental design to isolate moral emotions

To investigate these questions, the research team designed a controlled experimental paradigm that allowed them to independently manipulate harm and responsibility while measuring emotional responses, decision-making, and brain activity.

Participants took part in a novel decision-making game in which they believed they were one of four individuals performing a dots estimation task. If any of the deciders made an incorrect estimate, a “victim” would receive an electric shock of randomly determined intensity. In reality, the other deciders were confederates and the victim was fictitious, allowing precise experimental control.

Two variables were manipulated:

- Harm level, operationalized as the intensity of the electric shock on a scale from one to four.

- Responsibility level, operationalized by varying how many deciders made incorrect estimates, thereby diffusing or concentrating responsibility.

- After each trial, participants were given the opportunity to compensate the victim financially, providing a behavioral measure of reparative action.

This design allowed researchers to observe how different combinations of harm and responsibility elicited guilt and shame, and how those emotions translated into compensation decisions.

Behavioral findings: Harm drives guilt, responsibility drives shame

The results revealed a clear dissociation between the cognitive antecedents of guilt and shame.

The severity of harm caused to the victim had a stronger influence on participants’ feelings of guilt. As harm increased, guilt rose sharply, regardless of how responsibility was distributed among the group.

In contrast, participants’ sense of personal responsibility exerted a stronger influence on feelings of shame. When individuals felt more personally accountable for the harm, particularly when fewer others shared responsibility shame increased more strongly than guilt.

Crucially, guilt, but not shame, robustly predicted compensatory behavior. Participants who reported higher levels of guilt were significantly more likely to offer greater financial compensation to the victim. This finding reinforces the established link between guilt and altruistic, reparative action.

Shame, while emotionally intense, was less effective at translating into cooperative behavior.

Computational modeling and responsibility diffusion

To further understand how harm and responsibility were integrated before influencing compensation decisions, the researchers employed computational modeling.

The modeling results indicated that individuals combine harm and responsibility in a manner consistent with responsibility diffusion, a well-known phenomenon in social psychology. When responsibility is shared among a group, individuals tend to feel less personally accountable and adjust their behavior accordingly.

This integration occurs before emotional experience translates into action, suggesting that moral decision-making follows a structured computational process rather than an impulsive emotional reaction.

Neural mechanisms underlying guilt and shame

Participants underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while making compensatory decisions, allowing the researchers to identify neural correlates of guilt- and shame-driven behavior.

Several key findings emerged:

- The posterior insula, a region associated with processing inequity and aversive emotional states, encoded the integration of harm and responsibility.

- The striatum, a region involved in value computation and decision-making, also reflected this integration, linking moral evaluation to behavioral output.

Most importantly, guilt- and shame-driven compensatory decisions recruited distinct neural activity patterns.

Shame-driven decisions were more strongly associated with activation in the lateral prefrontal cortex, a region implicated in cognitive control and behavioral regulation. This suggests that acting under shame may require greater effortful control, possibly reflecting internal conflict or attempts to manage social evaluation.

These findings demonstrate that guilt and shame are not merely different labels for similar emotional states, but are supported by partially distinct neural systems.

Broader implications for mental health and society

The study’s findings carry significant implications across multiple domains.

In psychiatry and clinical psychology, the distinction between guilt and shame is critical. Excessive or chronic shame is strongly associated with mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and stress-related conditions. Understanding its neural basis may inform targeted interventions aimed at reducing maladaptive shame while preserving guilt’s adaptive role.

In public policy and ethics, the findings help explain why appeals to responsibility may sometimes backfire. Interventions that induce shame rather than guilt may suppress cooperation rather than promote it.

In neuroscience, the study advances a computational and neural account of moral emotions, bridging affective experience, cognition, and behavior within a unified framework.

Limitations and future directions

The authors acknowledge several limitations. While fMRI reveals correlational neural activity, it cannot establish causal relationships. Future studies using techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) will be necessary to determine whether specific brain regions play a causal role in guilt- and shame-driven behavior.

Further research may also explore how these neural mechanisms vary across cultures, developmental stages, and clinical populations.

Conclusion: From emotion to action

This study represents a major step forward in understanding how moral emotions guide human behavior. By disentangling the cognitive triggers and neural mechanisms of guilt and shame, the researchers provide a clearer picture of how humans navigate social norms, responsibility, and repair.

Guilt emerges as a powerful driver of altruistic behavior, closely tied to the perception of harm. Shame, more strongly linked to responsibility and self-evaluation, recruits different neural systems and leads to less consistent cooperation. Together, these findings offer a more nuanced understanding of conscience, not as a single emotional voice, but as a complex neural system balancing harm, responsibility, and social repair.

In doing so, the research illuminates how deeply moral emotions are woven into the architecture of the human brain.