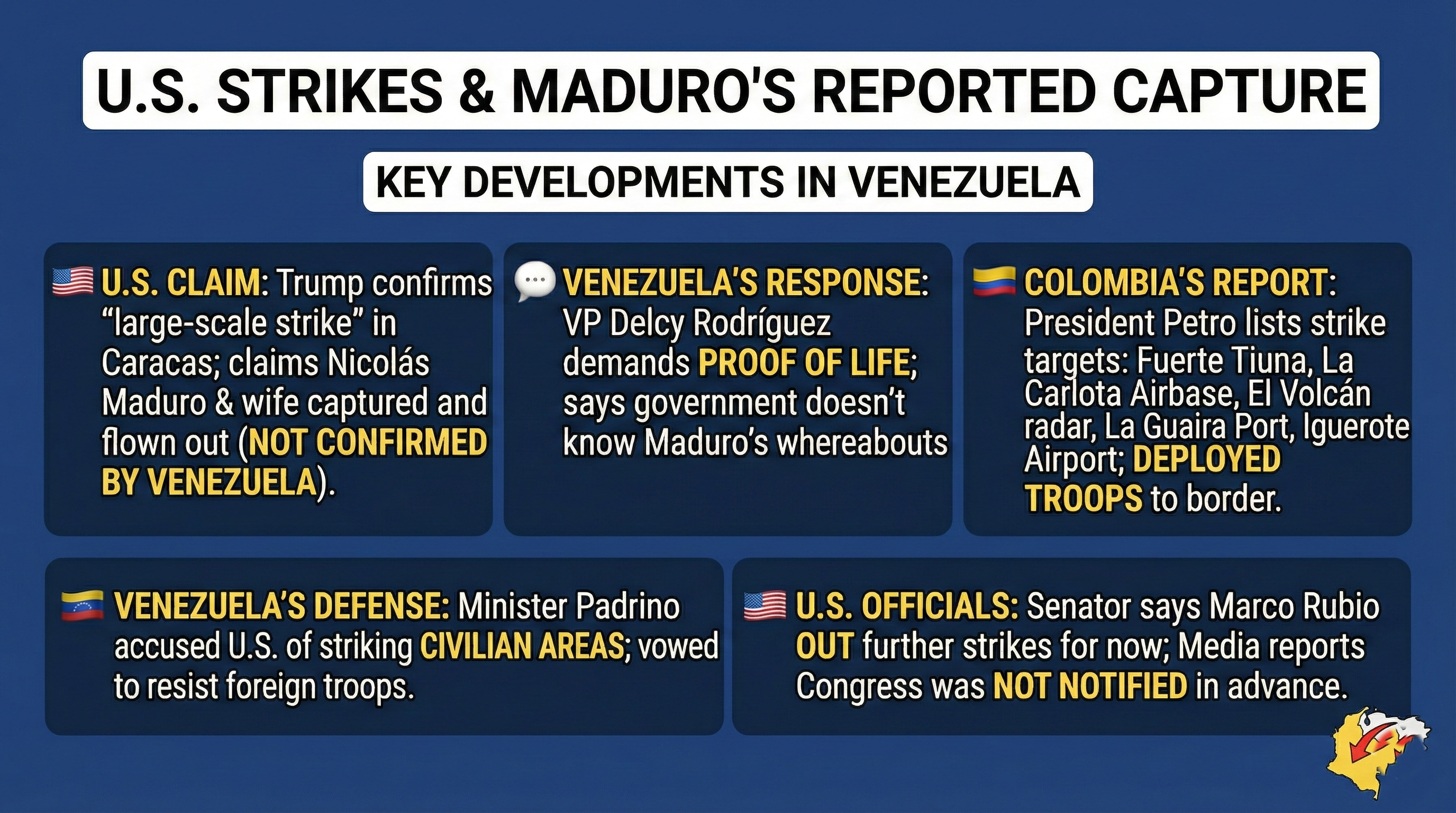

A time bound account of sanctions disputed elections counter narcotics justification. And the January 2026 US air strikes on Caracas. […]

AI-based sandbox provides insights into the evolution of visual systems

The diversity of visual systems observed in nature reflects a series of evolutionary trade-offs rather than a single optimal solution to perception. In vertebrates, including humans, vision is mediated by a camera-type eye capable of high-resolution image formation and fine object discrimination. Arthropods, by contrast, rely on compound eyes that sacrifice spatial acuity in favor of rapid temporal resolution and expansive visual fields. Although these architectures have been extensively characterized anatomically and physiologically, the evolutionary logic that led to their divergence remains only partially understood. In medical and neuroscience research, this gap persists because evolutionary processes cannot be directly manipulated or experimentally replayed.

A recent methodological advance developed by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and collaborating institutions provides a new experimental framework for investigating this problem. By integrating evolutionary algorithms with embodied artificial intelligence, the researchers created a system in which visual organs and perceptual strategies emerge gradually across generations of artificial agents. These agents are placed in controlled environments that impose specific perceptual tasks and resource constraints, allowing selective pressures to shape both sensory morphology and neural computation.

This work, reported in Science Advances, offers a mechanistic approach to studying vision evolution that complements traditional comparative methods. By enabling direct manipulation of environmental and task variables, the framework allows researchers to test how different selective pressures favor distinct visual architectures. From a medical science perspective, the findings have relevance beyond evolutionary theory, informing our understanding of sensory system efficiency, neural resource allocation, and the biological constraints that shape normal and pathological vision.

Why Vision Evolution Is So Hard to Study

Vision is not a single problem. It is a family of solutions shaped by ecology, physics, and survival needs. Light behaves the same everywhere, but animals do not. Some species need to detect motion quickly to escape predators. Others need fine visual detail to distinguish edible plants from toxic ones. Still others rely on vision to track prey, navigate complex terrain, or recognize members of their own species.

Humans evolved camera-type eyes with high acuity, color discrimination, and depth perception, optimized for daytime activity and complex object recognition. In contrast, insects evolved compound eyes that sacrifice resolution for wide fields of view and exceptional motion sensitivity. Both designs work remarkably well, but for different tasks.

The difficulty for scientists is that evolution leaves no experimental control group. Researchers cannot rewind the clock, change one environmental variable, and see how eyes would have evolved differently. Fossils preserve bone better than soft tissue, and eyes rarely fossilize in detail. Comparative biology tells us what exists, but not always why it emerged instead of something else.

This is the gap the new framework aims to fill.

A Computational “Sandbox” for Evolution

The MIT-led team approached the problem by asking a deceptively simple question: What if we let vision systems evolve again but inside a computer?

Their framework creates embodied AI agents that live in simulated environments. These agents must perform survival-like tasks such as navigating toward goals, finding food, tracking prey, or discriminating between objects. Vision is not predesigned. Instead, each agent starts with the simplest possible visual system: a single photoreceptor that captures light from the environment.

From there, evolution takes over.

To make this possible, the researchers translated the physical components of a camera sensors, lenses, apertures, optical layouts, and neural processors into learnable parameters. These parameters are encoded genetically, allowing them to mutate and recombine across generations. Over time, agents that see better for their task earn higher rewards and are more likely to pass on their visual traits.

Kushagra Tiwary, a graduate student at the MIT Media Lab and co-lead author of the study, describes the framework as a way to ask questions that are normally impossible to test. While evolution cannot be replayed in the real world, it can be recreated in a constrained, interpretable form.

The sandbox is not intended to simulate the universe atom-by-atom. Instead, the team carefully selected the ingredients that matter most for vision optics, neural processing, and environmental constraints and allowed evolution to work within those boundaries.

How the Framework Works

At the core of the system is an evolutionary algorithm combined with reinforcement learning.

Each agent has:

- A visual morphology (eye placement and field of view)

- Optical properties (number of photoreceptors, light sensitivity, and optical structure)

- A neural network that processes visual input and drives behavior

These features are controlled by different classes of “genes”:

Morphological genes determine where eyes are placed and how the agent views the world.

Optical genes define how light is captured, including the number and arrangement of photoreceptors.

Neural genes control learning capacity and information processing.

Within a single lifetime, an agent learns through reinforcement learning, trial and error guided by rewards. Across generations, genetic evolution reshapes the visual system itself.

Crucially, each environment includes constraints, such as limits on the number of pixels or computational resources. These constraints mirror real-world pressures like energy efficiency, physical size, and the physics of light. As Brian Cheung, a co-senior author of the paper, notes, bigger systems are not always better. Beyond a certain point, adding more neural capacity provides no advantage and simply wastes resources, a finding that echoes biological reality.

Tasks Shape Eyes: Key Experimental Findings

When the researchers tested the framework, a striking pattern emerged: tasks strongly determined the type of eyes that evolved.

Navigation Leads to Compound Eyes

Agents tasked primarily with navigation, moving efficiently through space and avoiding obstacles, tended to evolve compound eye-like systems. These eyes featured many individual sensing units, low spatial resolution, and wide fields of view. This design maximized spatial awareness and motion detection, closely resembling the eyes of insects and crustaceans.

Object Discrimination Favors Camera-Type Eyes

In contrast, agents focused on identifying or distinguishing objects evolved camera-type eyes with concentrated frontal acuity. These systems prioritized detail over coverage, mirroring the vertebrate eye with its retina, lens, and iris.

Bigger Brains Are Not Always Better

Another important insight was that visual performance does not scale indefinitely with neural size. Physical constraints such as the number of photoreceptors, limit how much information can enter the system. Once that bottleneck is reached, additional processing power offers diminishing returns. In evolutionary terms, unnecessary neural tissue would be metabolically expensive and therefore selected against.

Together, these results provide computational evidence for a long-standing hypothesis in evolutionary biology: vision systems evolve to solve specific ecological problems, not to maximize visual fidelity.

Why Humans Have the Eyes We Do

The framework cannot definitively answer why humans evolved their particular eyes, but it offers a compelling explanation grounded in task demands.

Human ancestors faced environments where object recognition, depth perception, social interaction, and fine motor coordination mattered greatly. Identifying edible plants, recognizing faces, judging distances, and manipulating tools all favor high-resolution, forward-facing vision. The sandbox experiments show that when these kinds of tasks dominate, camera-type eyes naturally emerge.

In other words, our eyes are not “better” than insect eyes. They are simply better suited to the problems our ancestors needed to solve.

Implications for Medical Science

Although the framework was developed in the context of AI and robotics, its implications for medical science are significant.

First, it provides a new way to study structure–function relationships in vision. By observing which eye designs emerge under specific constraints, researchers can better understand why certain visual impairments are so debilitating and why others are more easily compensated.

Second, the work may inform the design of visual prosthetics. Retinal implants and artificial vision systems must operate under severe constraints, including limited resolution and energy supply. Insights from evolved AI vision systems could guide more efficient designs that prioritize useful information over raw detail.

Third, the framework offers a model for studying neurodevelopmental trade-offs. The finding that bigger brains are not always better resonates with conditions where neural resources are misallocated or inefficiently used.

Beyond Biology: Robots, Vehicles, and Wearables

One of the most immediate applications of this research lies in engineering.

Modern cameras are often designed for human aesthetics rather than task efficiency. Autonomous vehicles, drones, and robots do not need cinematic images; they need reliable, fast, and energy-efficient perception. The sandbox framework can help identify task-specific vision systems that balance performance with manufacturability and power constraints.

For example:

Drones may benefit from insect-like compound vision optimized for motion detection.

Surgical robots may require narrow, high-acuity vision similar to camera-type eyes.

Wearable devices could adopt hybrid designs inspired by evolved systems.

By letting vision systems evolve rather than engineering them from scratch, designers may discover unconventional solutions that outperform traditional designs.

A New Way of Doing Science

Perhaps the most profound contribution of this work is methodological. The framework enables scientists to ask “what-if” questions that were previously unanswerable. What if early animals had faced different lighting conditions? What if energy constraints were tighter? What if object recognition mattered more than navigation?

As Tiwary notes, this imaginative approach to science expands the scope of inquiry. It moves research away from narrow optimization problems and toward broader exploration of possibility spaces.

Future plans include integrating large language models into the framework, allowing researchers to interact with the simulator more intuitively and explore even richer evolutionary scenarios.

Conclusion

The scientific sandbox developed by MIT researchers does not replace traditional evolutionary biology. Instead, it complements it by offering a controlled, repeatable, and deeply insightful way to explore how vision systems emerge under pressure.

By recreating evolution in silico, scientists are learning not only why certain eyes exist, but why countless other possible eyes do not. The result is a clearer understanding of vision as an adaptive interface one shaped by tasks, constraints, and survival, rather than by any universal blueprint.

For medicine, robotics, and neuroscience alike, this work represents a rare convergence of imagination and rigor. It reminds us that evolution is not just history, it is a design process still worth studying, one virtual generation at a time.