The human brain does not age along a single, uniform trajectory. Instead, brain ageing represents a spectrum of biological outcomes […]

Prehistory: Primitive man and the first Villages in Indian region

‘The development in human beings towards societies and village’

Primitive Man in India

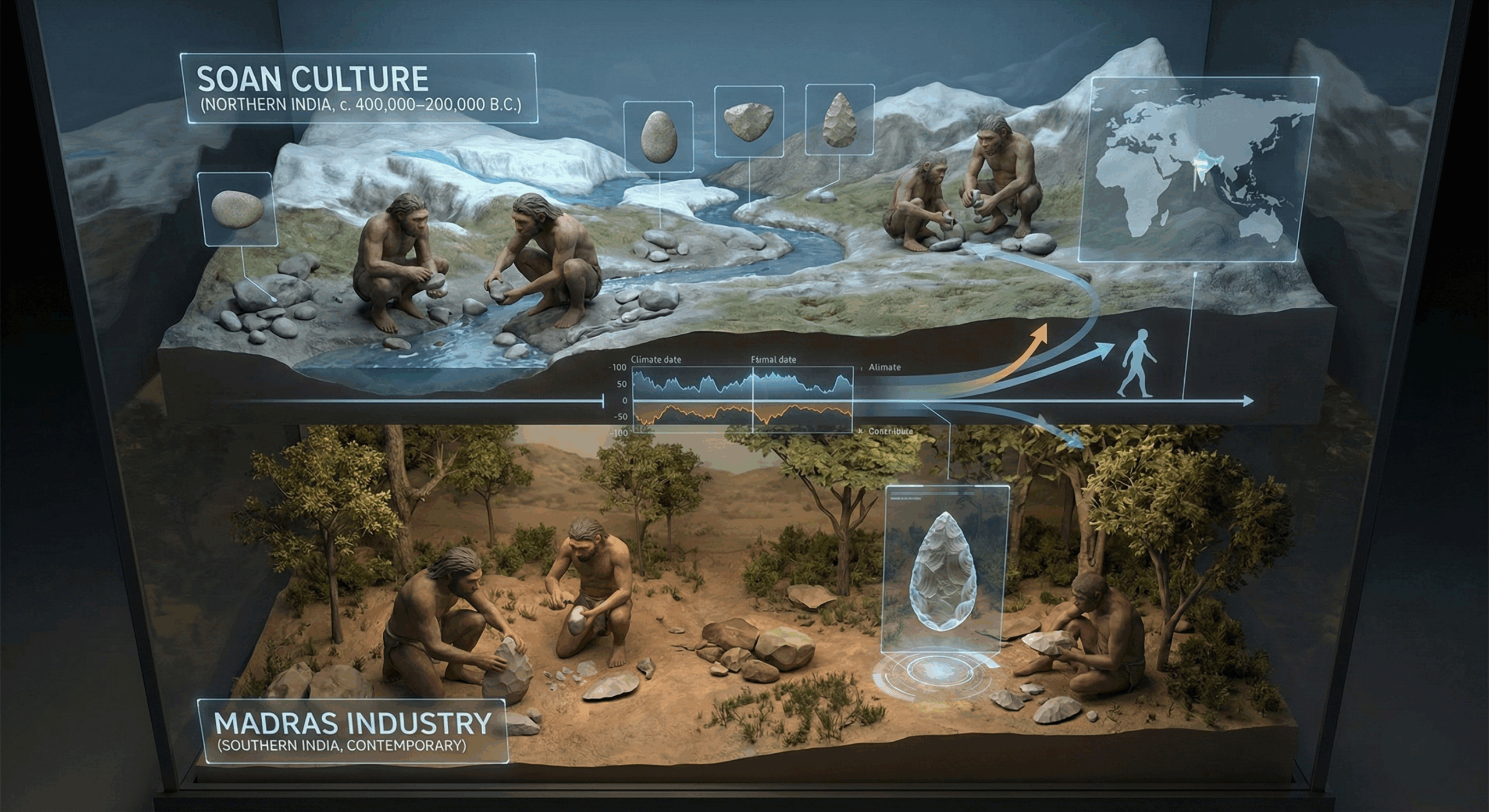

Long before history was written northern India like prehistoric Europe, passed through ice ages, and after the second interglacial period (c. 4,00,000 to 2,00,000 BCE) the earliest human traces appeared in India in the form of Paleolithic pebble tools, found mainly in the Soan Valley of Punjab, giving rise to the Soan culture, whose tools closely resembled those found across England, Africa, and China, showing a shared Old World Technological tradition.

In India, no human skeletal remains were found with these Soan tools, but similar industries elsewhere are known to belong to primitive anthropoid humans, such as Pithecanthropus in Java and China, suggesting that the earliest tool makers in India may not have been fully modern humans.

At roughly the same time, or slightly later, a second prehistoric stone industry developed in southern India, known as the Madras industry, whose people made core tools and finely shaped hand-axes by striking flakes from large pebbles, showing greater technical control than the soan tool makers.

The Madras industry shows close similarities with core tool cultures of Africa, Western Europe and southern England, and unlike the Soan culture, it is associated elsewhere with true Homo sapiens, indicating a more advanced human type in southern India.

During this period, the Ganges Valley was still geologically young, possibly covered by a shallow sea but occasional finds of tools from one culture in the region of the other suggest limited contact, lightly through Rajasthan, between northern and Southern prehistoric groups.

These palaeolithic humans lived in India for many millennia, surviving as hunters and food gatherers moving in small nomadic bands, using stone tools, fire animal skins, bark and leaves and possibly domesticating the wild dog, which lingered near their campfires.

Over long ages, homo sapiens continued in India, gradually improving skills and techniques and eventually producing microliths, tiny stone blades and arrowheads found widely from the northwest frontier to southern India, showing continuity and adaptation, rather than sudden cultural breaks.

Microlithic tools

Microlithic tools in India resemble those of the Near East and Africa, though their exact chronological relationship remains unclear, and in parts of the Deccan, microliths are found together with polished stone axes, showing overlapping technologies.

In some remote regions of the Indian Peninsula, stone tools continued alongside metal tools and microliths were replaced by iron only around the beginning of the Christian era, indicating slow and uneven technological change.

A major transformation occurred between c. 10,000 and 6000 BCE when humans developed what Gordon Child called an “aggressive attitude to the environment”, learning agriculture, animal domestication, pottery making, weaving and the production of polished stone tools, marking the transition of the neolithic age.

Neolithic tools

Neolithic tools have been found across India, especially in the northwest and Deccan, often near the surface, and neolithic culture survived so long that some hill tribes emerged from the stage only recently, showing deep continuity in life ways.

The First Villages

The first permanent villages emerged after agriculture developed with the earliest settled villages in India, appearing in Balochistan and Lower Sindh, possibly by the end of the 4th Millennium BCE, later than similar developments in the Middle East.

Around 3000 BCE, the Indus Region and Baluchistan were very different climatically with dense forests, abundant rivers, wild elephants and rhinoceros supporting numerous agricultural villages, unlike the dry landscape seen today.

These early village communities lived in small settlements rarely more than a few acres-built mud-brick houses with stone foundations made well fired, painted pottery and even used copper tools showing a relatively high material culture.

Different village cultures developed in isolation due to mountain valleys and limited contact, producing distinct pottery styles such as red ware in the north and buff ware in the South, and following different burial practices.

Kulli Culture and Nal culture

In the Kulli culture of Makran, people cremated their dead, while the Nal Culture of the Brahul Hills practiced fractional burial, placing bones after partial burning or exposure, showing varied ritual beliefs.

Religion in these early villages centered on fertility cults, especially the worship of a mother Goddess whose terracotta figurines have been found widely while phallic symbols discovered in zhob culture sites suggest fertility symbolism similar to that of the Mediterranean and Middle East.

The bull often associated with mother goddess worship in ancient societies, appears frequently in figurines and pottery designs, especially in kulli and Rana Ghundai, showing symbolic continuity with other early agrarian cultures.

The Kulli people were skilled craftsman who made engraved stone boxes, likely used for cosmetics or perfumes, which were found in early Mesopotamian sites indicating maritime trade between India and the Middle East.

Painted pottery imitating Kulli designs has been found at Susa, but the absence of overland trade objects suggest that contact occurred by sea, making the kulli culture one of Indias earliest trading societies.

Conclusion

Thus, from Ice-age Hunters to settle farmers, primitive man in India evolved through continuous technological, social and religious development, closely connected to global prehistoric patterns, yet shaped by Indias unique geography and long cultural continuity.

Leave a Reply