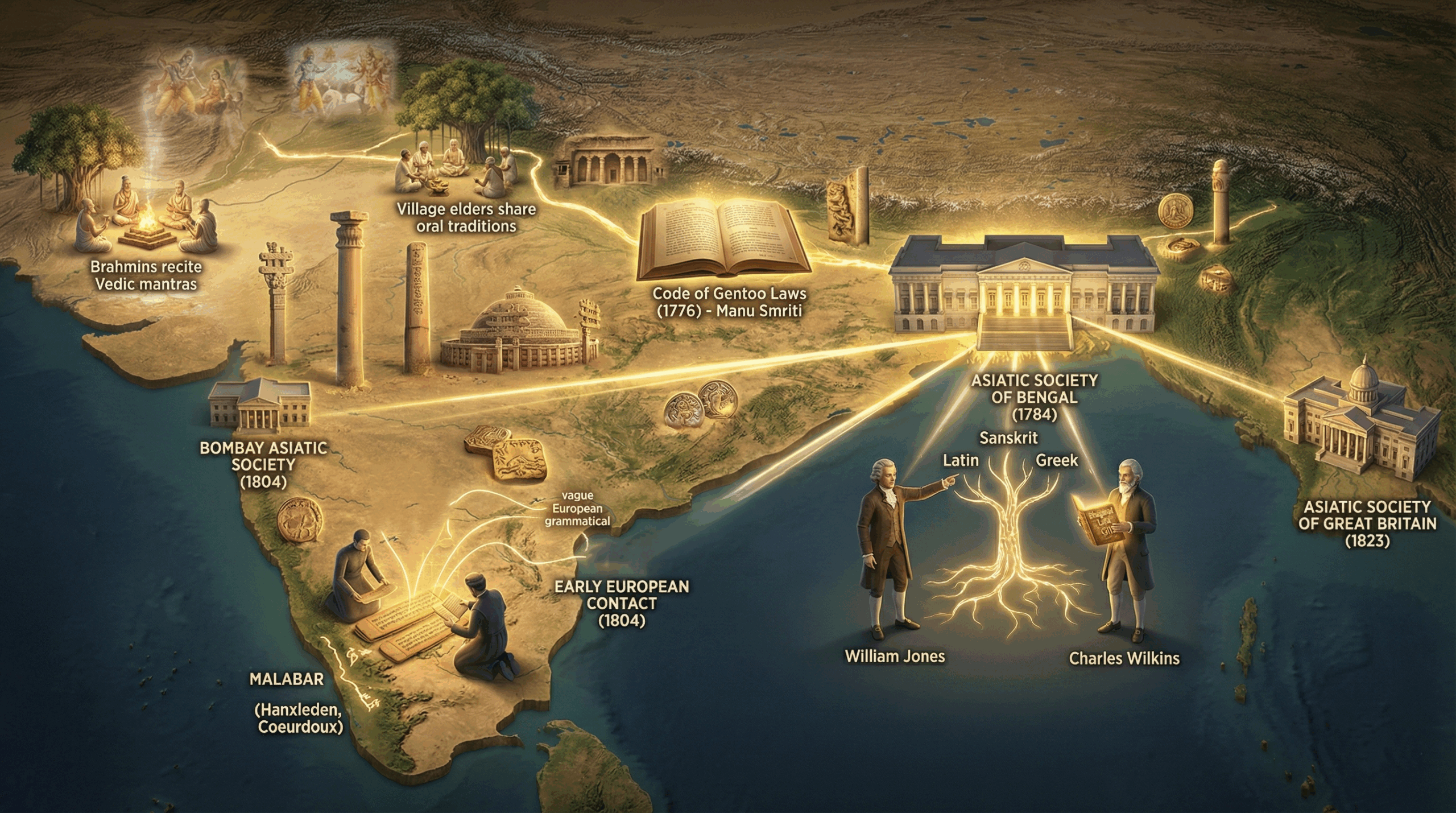

‘How the ancient history of India in modern times came to be noticed’ Introduction Ancient Indian civilization was unlike those […]

India’s Republic Day red carpet: How the chief guest reflects foreign policy

Every year on 26 January, India pauses to commemorate one of the most important milestones in its modern history the day it adopted its Constitution and formally became a sovereign republic. Republic Day is not merely a national holiday marked by flags and speeches, it is a carefully choreographed expression of India’s identity, values, and global position.

In 2026, India marks its 77th Republic Day, continuing a tradition that began in 1950 when the newly independent nation chose constitutional democracy as the foundation of its future. Over the decades, the celebrations have grown into one of the largest and most visually striking national events in the world, blending military strength, cultural diversity, and diplomatic symbolism into a single spectacle.

At the centre of these celebrations is the grand parade held in New Delhi, along the iconic Kartavya Path, formerly known as Rajpath, or King’s Avenue during British rule. The transformation of the name itself reflects India’s journey from colonial rule to self-determination. On this wide ceremonial boulevard, thousands of soldiers march in perfect formation, tanks roll past cheering crowds, fighter jets thunder across the sky, and vibrant cultural tableaux representing different states glide through the heart of the capital.

While the parade is impressive in scale and discipline, much of the attention is often drawn not just to what happens on the road, but to who is seated on the main dais. This year, occupying the most prominent seats alongside India’s President are European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and European Council President António Costa. Their presence places the European Union at the centre of one of India’s most prestigious state ceremonies.

More Than a Seat of Honour

The position of the chief guest at India’s Republic Day parade is far more than ceremonial protocol. Traditionally, the guest of honour is seated closer to the President than even the senior-most members of the Indian government. Over time, this symbolic positioning has come to represent something deeper, India’s diplomatic priorities and strategic messaging to the world.

Experts argue that the choice of chief guest offers a clear signal of which relationships India seeks to strengthen or highlight at a particular moment. In this sense, the Republic Day guest list acts as a mirror of India’s evolving foreign policy.

This tradition dates back to India’s very first Republic Day in 1950, when Indonesia’s then President Sukarno was invited as the inaugural chief guest. In its early years, India focused heavily on building solidarity with other newly independent nations across Asia and Africa. This reflected the broader spirit of the post-colonial world, where emerging states sought mutual cooperation outside the influence of traditional Western powers.

Over the decades, the profile of guests expanded to include leaders from almost every major region of the world, from neighbouring countries like Bhutan and Sri Lanka to global powers such as the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Russia.

One of the most notable moments came in 1961, when Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip attended the parade. The visit was symbolic, reflecting the long and complex relationship between India and the UK, former coloniser and former colony, now linked by history, institutions, and evolving strategic ties.

In fact, the United Kingdom has featured as chief guest on five occasions, more than most countries. France and Russia (formerly the Soviet Union) have also been invited nearly five times each, underlining India’s long-standing strategic partnerships with both nations, particularly in defence and diplomacy.

How India Chooses Its Chief Guest

Despite the high visibility of the event, the process of selecting the Republic Day chief guest remains largely behind closed doors. According to former diplomats and media reports, the process usually begins within the Ministry of External Affairs, which prepares a shortlist of potential invitees based on diplomatic priorities.

The final decision, however, rests with the Prime Minister’s Office. Once a name is finalised, official communication is sent to the selected country, a process that can take several months of coordination.

A former foreign ministry official, speaking anonymously, explained that multiple factors are considered during the selection. These include strategic objectives, regional balance, historical ties, and whether a particular country has been invited in the recent past.

Former Indian ambassador to the United States, Navtej Sarna, also emphasised the complexity of the decision-making process. According to him, it is always a careful balancing act between major global powers, important partners, and neighbouring states. Practical considerations, such as the availability of the foreign leader, also play a crucial role.

In other words, the guest list is never random. It is a calculated diplomatic statement.

From Obama to the European Union

One of the most historic moments in recent years was in 2015, when Barack Obama became the first sitting US President to attend India’s Republic Day parade. His presence marked a major milestone in Indo-US relations and symbolised a growing strategic partnership between the two democracies.

Foreign policy analyst Harsh V Pant believes that the changing list of chief guests reflects India’s shifting engagement with the global order. According to him, the presence of the European Union’s top leadership this year clearly signals India’s intention to deepen its ties with the EU.

Pant suggests that the visit could also coincide with major economic developments, including the possible announcement of a trade deal. Such a move would indicate that India and the European bloc are aligning more closely in response to current geopolitical challenges.

This becomes especially significant in the context of India’s ongoing trade negotiations with the United States. Talks between the two countries have continued for nearly a year, but relations have faced strain after the US imposed 50% tariffs on Indian goods the highest in Asia. These tariffs also include penalties linked to India’s purchase of Russian oil.

Against this backdrop, inviting the EU leadership as chief guests sends a subtle but clear message: India is actively diversifying its global partnerships and reinforcing its engagement with multiple power centres.

Pant notes that the choice of chief guest often reflects India’s priorities at a specific moment whether it wants to focus on a particular region, highlight a strategic shift, or mark a diplomatic milestone.

A notable example came in 2018, when leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) were invited collectively as chief guests. It was the first time a regional grouping received the honour, marking 25 years of India’s engagement with ASEAN and highlighting India’s growing focus on Southeast Asia.

When Absences Speak Louder Than Invitations

Interestingly, the Republic Day guest list also tells stories through its omissions.

Pakistan, for instance, was invited twice as chief guest in the early years. However, after the two countries went to war in 1965, Pakistani leaders have not been invited again, a reflection of enduring tensions and unresolved conflicts.

Similarly, China’s presence has been rare. The only time a Chinese leader attended the parade was in 1958, when Marshal Ye Jianying visited India. Just four years later, the two countries went to war over their disputed border, and since then, China has not featured on the guest list.

These absences highlight an important reality: Republic Day diplomacy is not just about celebrating friendships, it also reflects fractures, rivalries, and geopolitical realities.

A Different Kind of Military Parade

While India’s Republic Day parade includes a strong military component, analysts argue that it stands apart from similar displays around the world.

In many countries, national military parades commemorate victories in war. Russia’s Victory Day celebrates the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II. France’s Bastille Day marks the French Revolution and the collapse of monarchy. China’s military parade celebrates its victory over Japan during World War II.

India’s parade, however, is fundamentally different.

According to Harsh V Pant, India does not celebrate a military triumph. Instead, it celebrates the coming into force of its Constitution and its transformation into a constitutional democracy.

This distinction gives India’s Republic Day a unique moral and political character. The event is not about conquest or domination, it is about law, citizenship, and democratic governance.

Power Meets Diversity

Another feature that sets India’s parade apart is the way it blends military strength with cultural representation.

Alongside tanks, missiles, and marching battalions, the parade also showcases colourful tableaux representing India’s states and union territories. These floats highlight regional traditions, festivals, folk dances, historical figures, and social themes, projecting an image of unity in diversity.

Unlike many Western military parades that focus almost exclusively on armed forces, India’s Republic Day presents both power and plurality, hard strength balanced with soft culture.

This dual projection is deliberate. It allows India to present itself not only as a capable military power, but also as a civilisation rooted in history, culture, and democratic values.

The Human Side of Diplomacy

Beyond strategic symbolism and geopolitical messaging, Republic Day also leaves a lasting personal impression on visiting leaders.

A former Indian official recalled that when Barack Obama and his wife Michelle attended the parade, they were particularly fascinated by the camel-mounted contingents of the Indian military, a uniquely Indian sight that stood out even amid the grandeur of the ceremony.

Such moments remind us that beneath the layers of diplomacy and protocol, these events also create human memories. Visiting leaders do not just observe India as a geopolitical entity, they experience its colours, rhythms, traditions, and people.

In many ways, this is where Republic Day’s real power lies. It is not just a display of military might or diplomatic signalling. It is a carefully constructed narrative about what India stands for: a nation born from colonial rule, shaped by constitutional ideals, proud of its diversity, and increasingly confident on the global stage.

A Living Symbol of Modern India

Seventy-seven years after becoming a republic, India’s Republic Day remains more than a ritual. It is a living symbol of India’s journey, political, cultural, and diplomatic.

From Sukarno in 1950 to Obama in 2015, and now the leadership of the European Union, the chief guest tradition has evolved into a subtle but powerful tool of foreign policy. Each invitation tells a story. Each absence speaks volumes.

At the same time, the parade itself continues to reflect India’s core identity: not a nation defined by military victories, but by constitutional ideals, democratic aspirations, and cultural richness.

As fighter jets roar overhead and soldiers march down Kartavya Path, what India ultimately celebrates is not just its power but its promise. A promise made in 1950, and renewed every year, that the republic belongs to its people and to the principles enshrined in its Constitution.