For centuries, the heart was viewed as an autonomous muscular pump remarkably resilient, yet ultimately doomed to age through mechanical […]

Development of ancient Indian historiography

‘How the ancient history of India in modern times came to be noticed’

Introduction

Ancient Indian civilization was unlike those of Egypt, Mesopotamia or Greece, because its cultural traditions continued without interruption Into modern times. In Egypt and Iraq, ordinary people had lost all memory of their ancient past before archaeology began. In Greece, even educated people hadonly a vague idea of classical Athens. In India, however, society remained conscious of its antiquity.

Village legends recalled Chiefs who lived around 1000 BC and Brahmans continued to recite hymns composed much earlier. Along with China, India possessed the oldest continuous cultural tradition in the world. Yet continuity did not mean history. India preserved memory through epics, puranas, rituals and customs, but not through modern historical writing. As a result, until the late 18th century, there was no critical chronological study of Indias ancient past.

Jesuits precursors and linguistic clues

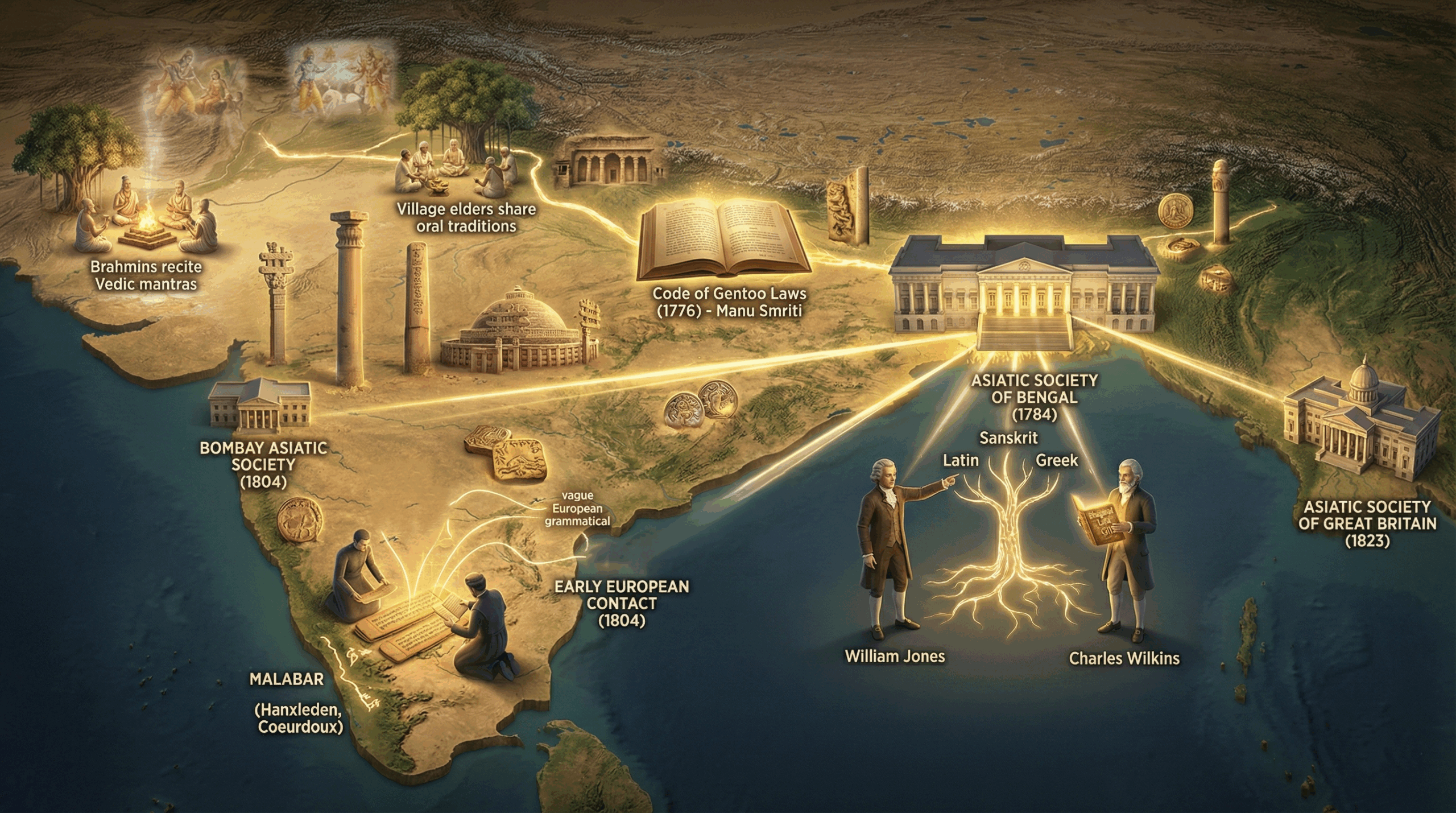

Some Jesuit missionaries learned Sanskrit, but their work remained isolated. Father Hanxleden working in Malabar between 1699 and 1732 prepared the first Sanskrit grammar in a European language, though it remained unpublished. Father Coeurdoux, In 1767, recognised the relationship between Sanskrit and European languages, but still explained it through biblical descent. These efforts produce linguistic insight, not historical reconstruction.

Colonialist approach and its contribution.

Before British rule, Indians preserved their past through hand epics Puranas, and semi biographical works. These writings were not modern historical research. Model research on ancient Indian history began only in the second half of 18th century and it began to serve British colonial needs.

In 1765 Bengal and Bihar came under the rule of East India Company. The British administration face the difficulty in governing because they did not understand Hindu law of inheritance. To solve this, in 1776, the Manusmriti was translated into English as a code of Gentoo laws. When its were attached to British judges to administer inducible law in Maldives, were attached to administering law Early historical study, therefore focused mainly on laws and customs.

These efforts led to the founding of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784 at Calcutta by Sir William Jones, a civil servant of the East India Company. He suggested that Sanskrit, Latin and Greek belong to the same language family. He translated Abhigyansakuntalam into English in 1789. In 1785, the Bhagavad Gita was translated into English by Wilkins. The Bombay Asiatic Society was founded in 1804, and the Asiatic Society of Great Britain was founded in London in 1823.

Between 1784 and 1794, foundational translations appeared:

- Bhagwad Geeta (Wilkins, 1784).

- Hitopadesa (1787)

- Sakuntala (Jones, 1789)

- Geeta Govinda (1792)

- Institute of Hindu law (Manu, 1794)

Jones emphasised the close relationship between Sanskrit, European languages and Iranian language. This encouraged Germany, France and Russia to develop Indological studies. During the first half of the 19 century, chairs of Sanskrit were established in Britain and other European countries.

European expansion of Indology (1795-1832).

After Jone’s, scholars such as Henry Colebrook and Horace Hayman Wilson continued textual research. Anquetil-Duperron translated the Upanishads from Persian (1786-1801).

Institutional growth followed:

- 1795: Ecole des Langues Orientales, Paris.

- 1803: Sanskrit first taught in Europe by Alexander Hamilton.

- 1814: First Sanskrit chair at College de France.

- 1818 onwards: Chairs in German universities

- 1832: Boden professorship at Oxford.

History was still text centred and elite, but it had become international.

Comparative philology and Max Mueller (19th century)

In 1816, Franz Bopp reconstructed the Indian European language family, making comparative philology a science. The Societe Asiatique (1821) and Asiatic society (1823) institutionalised oriental studies.

The greatest expansion of Indology came under F. Max Mueller, who worked mainly in England. He edited the rg veda and the sacred books of the east. Although some Chinese and Iranian texts were included, Indian texts dominated.

In introduction to these works, Mueller and other western scholars made generalisations. They claimed ancient Indians lack the sense of history and chronology, were accustomed to despotic rule, were absorbed into spiritual matters and lacked concern for worldly affairs. They argued Indians had no sense of nationhood or self-government.

These views where systematised by Vincent Archer Smith in his book ‘Early history of India (1904). It was the first systematic history of ancient India, and remained a textbook for about 50 years. Smith emphasised political history and supported imperialism. Nearly one third of his book dealt with Alexander’s invasion. He presented India as a land of despotism and claimed political unity. Came only under British rule. These interpretations denigrated Indian achievements and justified colonial rule. Although Indians showed weaker chronology than the Chinese, colonial generalisations were largely exaggerated and served propaganda purposes.

Archaeology and the material past (1837-1900)

Textual history was soon supplemented by material evidence in 1837, James Prinsep deciphered Brahmi scripts and read Ashokan edicts, giving history firm chronological anchors.

His colleague, Alexander Cunningham arrived in India in 1831. Appointed the first archaeological surveyor of India in 1862. He surveyed monuments and inscriptions until 1885 though methods were crude, Cunningham transformed history from text based study to material reconstruction.

Scientific excavation and the Indus Civilization. (1901-1931)

Large scale excavation began in the 20th century. In 1901, Curzon reformed the archaeological survey and appointed John Marshall.

Under Marshall:

- Archaeology became systematic

- Ancient cities were excavated

- History expanded beyond texts

The greatest discovery was Indus Valley Civilization. Seals first noticed by Cunningham at Harappa were followed by discovery that Mohenjo Daro in 1922 by RD Banerjee. Excavation from 1924 to 1931 revealed a pre-aryan urban civilization pushing Indian history far earlier than texts alone had suggested.

Nationalist approach and its contribution.

Rajendra Lal Mitra Published baby texts and wrote Indo Aryans. He adopted a rational approach. Some scholars argue that caste was similar to class systems in ancient and pre industrial Europe.

In Maharashtra, Ram Krishna Bhopal Bhandarkar reconstructed the political history of the Satavahanas and studied Vaishnavism and other sects. His work supported widow remarriage and opposed caste evils and child marriage. Biswanath Kashinath Rajwade travelled village to village, collecting Sanskrit manuscripts. These were published in 22 volumes. His 1926 Marathi work on the history of marriage remains a classic.

Pandurang Vaman Kane continued this tradition. His five-volume history of the Dharam Shastra systematically documented ancient social laws and Customs and enabled the study of long-term social processes.

To counter claims that India lacked political history. Scholars focused on quality and administration. Devdutt Ramakrishna Bhandarkar wrote on Ashoka and ancient political institutions using inscriptions. Himachandra Raychaudhary reconstructed history from the Mahabharat War (10th century. BC) to the end of Gupta Empire. He used comparative European methods, criticised VA Smith, and ended his narrative at the 6th century AD. His work showed scholarly rigour, but contained Brahmanical Bias, specially in criticism of Ashoka.

A stronger Hindu revivalist trend appeared In RC Majumder, editor of history and culture of the Indian people. Most Indian historians minimised Alexander’s invasion and emphasised Porous-Alexander dialogue and Chandragupta Maurya’s victory over Seleucus. Scholars like KP Jaiswal and AS Altekar overstated indigenous resistance to Shakas and Kushans, ignoring their integration into Indian society.

Jaiswal’s major contribution was disproving the myth of Indian despotism in Hindu polity (1924), he showed the existence of ancient republics. Though criticised by UN Ghoshal, his core argument is widely accepted.

Move towards non-political history

Al Basham questioned judging ancient India by modern standards. His ‘The wonder that was India’ (1951) shifted focus from politics to culture and civilization, and avoided colonial bias.

A more radical shift came with DD Kaushambi. In an introduction to the study of Indian history, 1957, he applied a materialist interpretation derived from Marxism. He analysed society, economy and culture through class and production relations and integrated archaeology and anthropology. Despite criticism, his works remain influential.

Over the last 40 years, historians have emphasised the social, economic and cultural processes and compare texts with archaeological evidence. Western historians no longer insist on foreign origins of all Indian culture but often emphasise continuity and stagnation, sometimes implying Indian society cannot change.

Conclusion, How Indian history was made

Indian history did not emerge fully formed. It moved from memory to text, from colonial law to linguistics, from imperial politics to archaeology, and finally to social and economic analysis. Each generation rewrote the past using new methods and new evidence. The development of Indian historiography is therefore not only the history of India, but the history of how India’s learned to study itself.