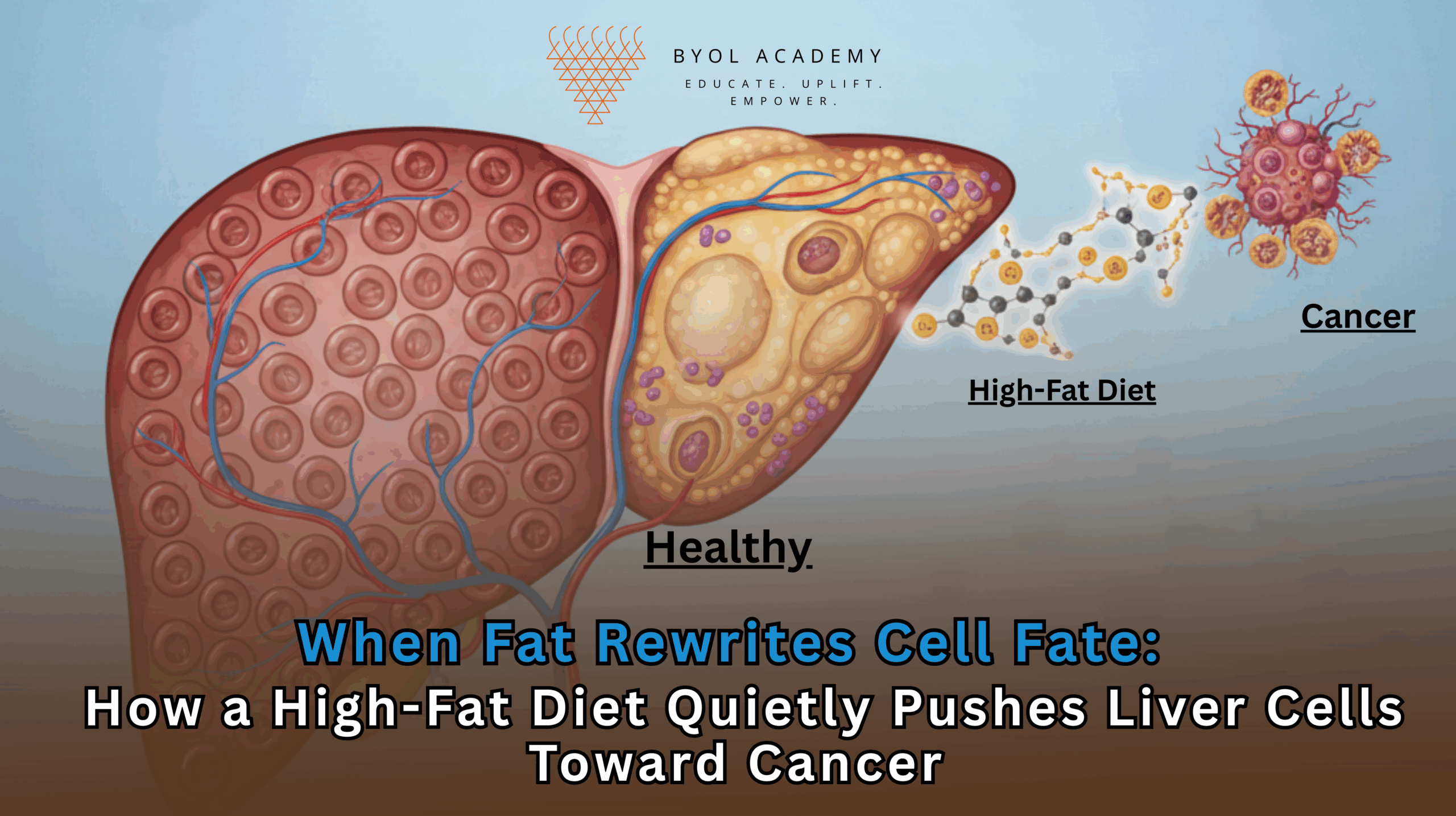

Liver cancer is one of the fastest-rising causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide, closely tracking the global surge in obesity, metabolic […]

Vibrating Nanoparticles Activated by Ultrasound Enhance Cancer Drug Delivery

Cancer continues to impose a substantial clinical and societal burden, ranking among the leading causes of death worldwide and in the United States. Although the therapeutic arsenal against cancer has expanded to include precision oncology, immune-based treatments, and molecularly targeted drugs, chemotherapy remains indispensable for many solid tumors. Yet its limitations are increasingly recognized as structural rather than pharmacological.

In many cases, chemotherapeutic agents are sufficiently potent in vitro but fail to reach effective concentrations throughout the tumor in vivo. This discrepancy has shifted attention toward the tumor microenvironment itself, particularly its mechanical and architectural features as a decisive factor in therapeutic resistance.

Tumor Stiffness as a Barrier to Treatment

Solid tumors are not passive collections of malignant cells. They are highly dynamic, mechanically rigid tissues formed through continuous interactions between cancer cells, stromal cells, extracellular matrix components, and aberrant vascular networks. One of the most striking features of many solid tumors is their increased stiffness compared to surrounding healthy tissue.

This stiffness arises from excessive deposition of extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen and fibronectin, increased cross-linking of matrix fibers, and dysregulated tissue remodeling. At the same time, tumors develop disorganized and fragile blood vessels that are prone to collapse under mechanical stress. Elevated interstitial fluid pressure further exacerbates this condition, creating an environment in which blood flow is uneven and molecular transport is severely restricted.

From a therapeutic standpoint, these physical properties represent a formidable barrier. Chemotherapeutic agents delivered through the bloodstream struggle to penetrate deep into the tumor mass. As a result, drug distribution becomes heterogeneous, with peripheral tumor cells receiving higher exposure while cells in the tumor core remain partially or entirely protected. This uneven exposure fosters drug resistance, promotes tumor survival, and contributes to disease progression and recurrence.

Limitations of Conventional Approaches to Improving Drug Delivery

Several strategies have been explored to overcome poor intratumoral drug delivery, including dose escalation, vascular normalization therapies, and enzymatic degradation of extracellular matrix components. However, each of these approaches carries significant limitations.

Increasing drug dosage often leads to unacceptable systemic toxicity, damaging healthy tissues such as bone marrow, gastrointestinal epithelium, and cardiac muscle. Pharmacological attempts to alter tumor vasculature have yielded mixed results and can produce unpredictable outcomes. Enzymatic approaches risk excessive tissue degradation and inflammation, raising safety concerns.

These challenges highlight the need for alternative strategies that can modify tumor structure in a controlled, localized, and reversible manner without inducing widespread damage.

Ultrasound as a Modality for Mechanical Tumor Modulation

Ultrasound has long been a cornerstone of clinical diagnostics, valued for its non-invasive nature, real-time imaging capability, and deep tissue penetration. Therapeutically, ultrasound has also been employed for tissue ablation, drug release, and vascular disruption. However, high-intensity ultrasound carries inherent risks, including thermal injury, damage to surrounding healthy structures, and unintended vascular effects that may increase the risk of metastasis.

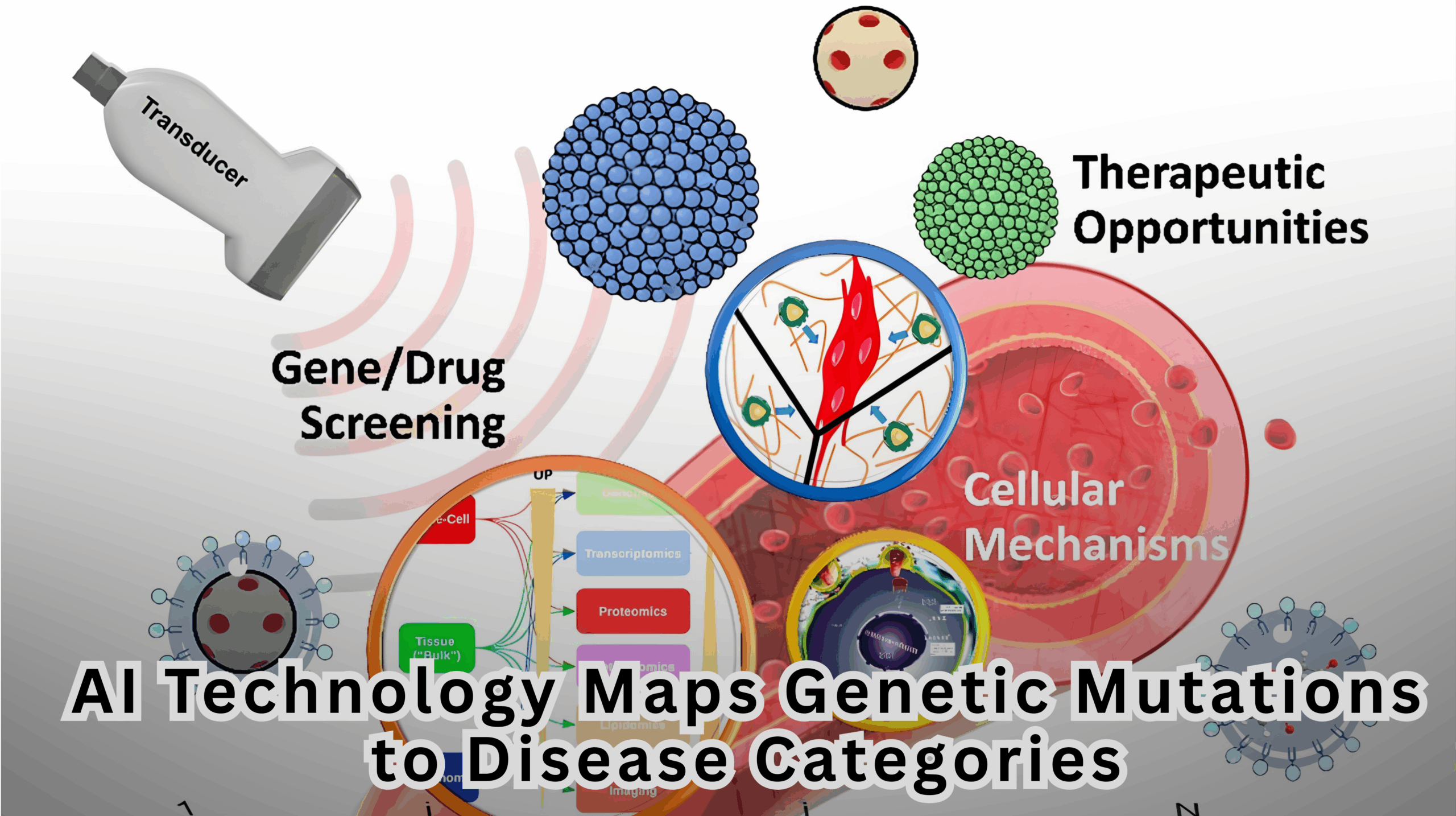

Recognizing both the power and limitations of ultrasound, researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder have pursued a fundamentally different approach. Rather than using ultrasound as a destructive force, they have repurposed it as a finely controllable mechanical stimulus. By pairing ultrasound with engineered nanoparticles, they aim to localize and amplify mechanical effects specifically within tumor tissue, enabling precise modulation of tumor stiffness.

Design Principles of Ultrasound-Responsive Nanoparticles

At the core of this strategy are sound-responsive nanoparticles engineered to interact dynamically with acoustic waves. These nanoparticles are approximately 100 nanometers in diameter, small enough to interact with cellular and extracellular components yet large enough to respond robustly to ultrasound stimulation.

Structurally, the particles consist of a silica core surrounded by a lipid-like coating. This design confers both mechanical stability and acoustic sensitivity. When exposed to high-frequency ultrasound, the particles oscillate rapidly, inducing localized acoustic cavitation in the surrounding fluid environment.

Acoustic cavitation involves the transient formation and collapse of microscopic vapor bubbles. Although cavitation is often associated with tissue damage at high intensities, when carefully controlled it can generate localized mechanical forces without producing significant heat or widespread disruption. In this context, cavitation acts as a tool for micro-scale tissue remodeling rather than destruction.

Crucially, the presence of nanoparticles lowers the ultrasound energy required to induce these effects. This allows clinicians to operate within a safer acoustic window, reducing the risk of collateral damage while preserving therapeutic efficacy.

Experimental Evidence from Tumor Model Systems

To investigate the biological consequences of this approach, researchers evaluated ultrasound-activated nanoparticles in both two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) tumor models.

In 2D cultures, where tumor cells grow as monolayers on rigid substrates, the application of ultrasound in the presence of nanoparticles resulted in extensive cellular damage and tissue disruption. While these findings confirmed the mechanical potency of the system, they also underscored the limitations of simplified culture models that lack a physiologically relevant extracellular matrix.

More revealing insights emerged from experiments conducted in 3D tumor cultures. These models replicate key features of in vivo tumors, including matrix composition, mechanical stiffness, and cell–cell interactions. In these systems, ultrasound-activated nanoparticles did not destroy tumor cells. Instead, they selectively reduced the density of extracellular matrix proteins surrounding the cells.

This remodeling led to a measurable decrease in tissue stiffness while preserving overall tissue architecture and cellular viability. The ability to soften tumors without inducing cytotoxicity represents a critical advance, as it suggests that mechanical modulation can be decoupled from tissue destruction.

Implications for Chemotherapy Delivery

Mechanical softening of tumor tissue has profound implications for drug delivery. Reduced stiffness lowers interstitial fluid pressure, alleviating compression on blood vessels and improving perfusion. As vascular function improves, chemotherapeutic agents can reach deeper regions of the tumor more effectively.

Enhanced perfusion and reduced matrix density also facilitate diffusion, enabling more uniform drug distribution. This uniformity is particularly important for preventing the survival of drug-shielded cell populations that can drive resistance and relapse.

Importantly, by improving delivery efficiency, this approach may allow effective treatment at lower drug doses, potentially reducing systemic toxicity and improving patient quality of life.

Safety Considerations and Therapeutic Precision

A key advantage of the nanoparticle-assisted ultrasound strategy is its safety profile. By enabling therapeutic effects at lower ultrasound intensities, the approach minimizes risks associated with vascular injury, inflammation, and unintended tissue damage.

Furthermore, ultrasound offers exceptional spatial control. Clinicians can precisely focus acoustic energy on specific tumor regions while sparing adjacent healthy tissue. When combined with image-guided systems, this precision aligns closely with the goals of modern precision oncology.

Clinical Applicability and Target Cancer Types

This approach is particularly well suited for solid tumors that are anatomically localized and accessible to focused ultrasound, including cancers of the prostate, bladder, breast, and ovary. These tumors can be targeted with high spatial accuracy, making them ideal candidates for mechanical modulation strategies.

Diffuse malignancies, such as hematologic cancers, may be less amenable due to the absence of a discrete tumor mass. Nonetheless, for a wide range of common and clinically challenging solid tumors, ultrasound-mediated tumor softening could serve as a powerful adjunct to existing therapies.

Translational Pathways and Future Directions

Current research efforts are extending this work into animal models to assess biodistribution, safety, and therapeutic efficacy in vivo. These studies will be critical for evaluating immune responses, clearance mechanisms, and long-term outcomes.

Future developments may involve functionalizing nanoparticles with targeting ligands such as antibodies or peptides. This would enable systemic administration and selective accumulation within tumors, further enhancing specificity. Once localized, externally applied focused ultrasound could activate the particles precisely where needed.

The convergence of advances in nanoparticle engineering, ultrasound physics, and real-time imaging positions this approach well for integration into clinical practice.

Redefining the Therapeutic Paradigm in Oncology

This work reflects a broader shift in oncology toward treating cancer not only as a genetic and molecular disease, but also as a physical and mechanical one. By recognizing tumor stiffness as a modifiable parameter, ultrasound-responsive nanoparticles introduce a new dimension to therapeutic design.

Rather than escalating drug potency or dosage, this strategy reshapes the tumor environment to make existing therapies more effective. If successfully translated, it could improve treatment outcomes, reduce toxicity, and expand therapeutic options for patients with resistant solid tumors.

Ultimately, this approach reinforces a growing principle in cancer research: overcoming malignancy may require not only attacking cancer cells directly, but also transforming the terrain in which they survive.