Neuroscience has long advanced by increasing the intensity of its gaze. To see deeper, faster, and with greater precision, researchers […]

When Fat Rewrites Cell Fate: How a High-Fat Diet Quietly Pushes Liver Cells Toward Cancer

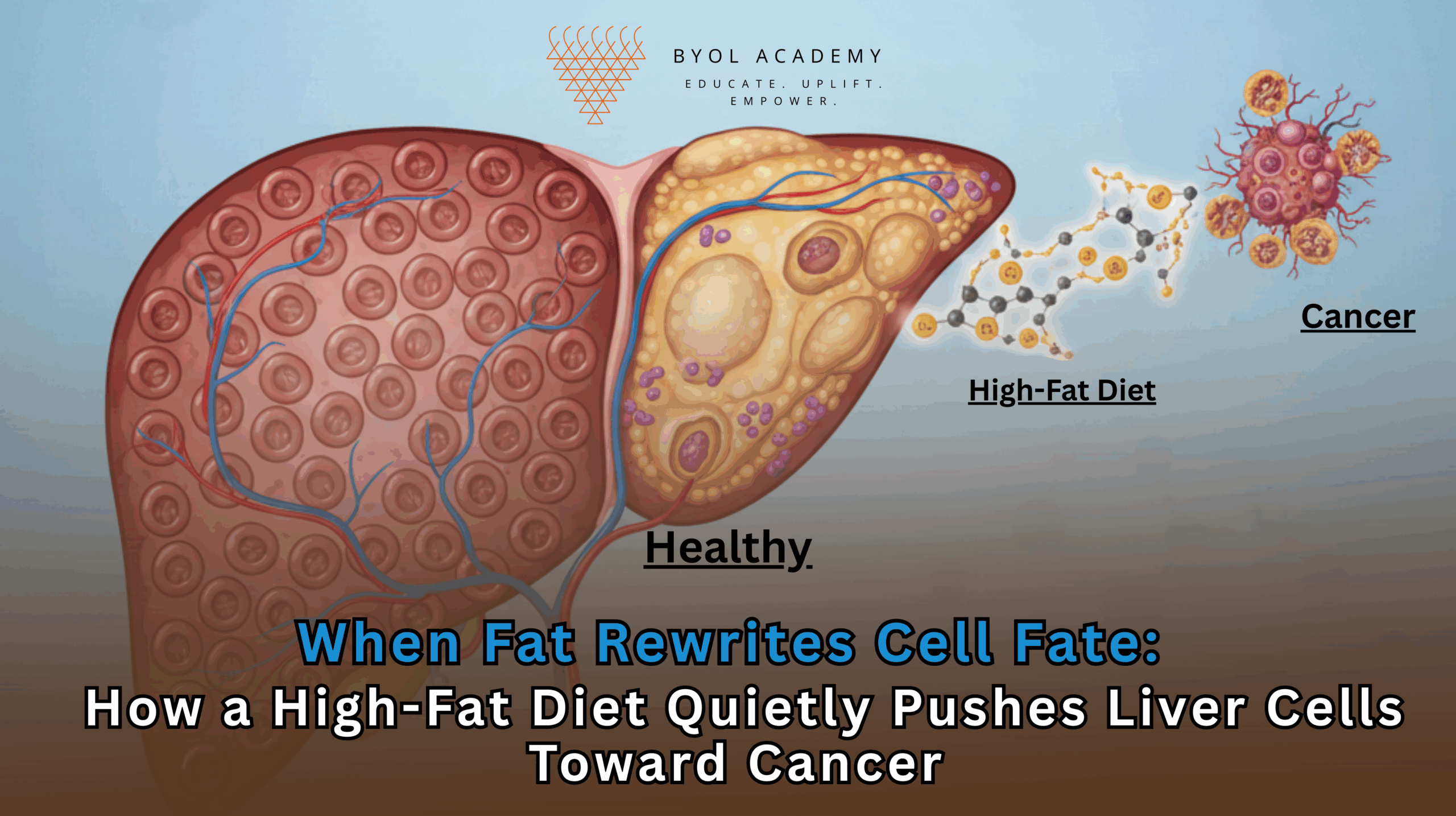

Liver cancer is one of the fastest-rising causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide, closely tracking the global surge in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and fatty liver disease. For years, clinicians have recognized a strong association between high-fat diets and hepatocellular carcinoma, yet the molecular chain of events linking dietary fat to cancer initiation has remained incomplete. A new study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), published in Cell, now provides a detailed mechanistic explanation: chronic exposure to a high-fat diet fundamentally rewires liver cells, pushing them backward into an immature, stem-like state that is uniquely vulnerable to cancer-causing mutations.

This research does more than describe correlation. It uncovers a step-by-step biological process through which metabolic stress reshapes cell identity, alters gene regulation, and accelerates tumorigenesis. In doing so, it reframes liver cancer as not merely a disease of genetic mutations, but as a long-term consequence of disrupted cellular differentiation driven by metabolic overload.

Metabolic Stress and the Liver’s Adaptive Limits

The liver sits at the crossroads of metabolism. Hepatocytes, the dominant cell type in the liver are highly specialized to manage lipid processing, glucose regulation, bile production, and detoxification. Their mature identity is maintained by tightly regulated gene expression programs that prioritize metabolic efficiency and tissue-level coordination over individual cell survival.

A high-fat diet places extraordinary stress on this system. Excess lipids accumulate within hepatocytes, triggering inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Over time, this environment leads to steatotic liver disease, previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which can progress to steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and ultimately liver cancer. Similar pathological trajectories can also be driven by chronic alcohol consumption, viral hepatitis, or other long-standing metabolic insults.

What the MIT study sought to understand was not just that liver disease progresses under metabolic stress, but how individual liver cells respond at the molecular level as this progression unfolds.

Tracking Cellular Identity in Real Time

To dissect these changes, the researchers fed mice a high-fat diet and analyzed their liver tissue at multiple stages of disease progression from early inflammation to fibrosis and finally cancer. Using single-cell RNA sequencing, they were able to observe gene expression changes in thousands of individual liver cells over time. This approach allowed unprecedented resolution, revealing how hepatocytes gradually altered their transcriptional programs in response to sustained fat exposure.

The results revealed a striking pattern. Early in disease progression, hepatocytes began activating genes associated with stress resistance, survival, and proliferation. These included genes that protect against apoptosis (programmed cell death) and promote cell cycle entry. From the perspective of an individual cell, this makes sense: survival under hostile conditions requires resilience and adaptability.

At the same time, however, hepatocytes progressively shut down genes essential for their normal physiological roles. Expression of metabolic enzymes, secreted liver proteins, and other hallmarks of mature hepatocyte function steadily declined. This loss was not abrupt but accumulated gradually over months, indicating a slow erosion of cellular identity.

As Constantine Tzouanas, a co-first author of the study, explains, this reflects a biological trade-off: cells prioritize immediate survival over long-term tissue function. What benefits the individual cell in the short term undermines the integrity of the organ in the long term.

Reversion to an Immature, Stem-Like State

The most consequential discovery was that hepatocytes exposed to a high-fat diet did not simply become dysfunctional, they de-differentiated. In other words, they reverted toward an immature, progenitor-like state resembling early developmental liver cells.

This reversion is significant because immature cells behave very differently from mature ones. They divide more readily, are less constrained by tissue-level controls, and possess epigenetic landscapes that are more permissive to gene expression changes. While such plasticity is essential during development and tissue repair, it becomes dangerous when sustained in adult organs.

“These cells have already turned on the same genes that they’re going to need to become cancerous,” Tzouanas notes. By shedding their mature identity, hepatocytes remove the brakes that normally restrain proliferation. Once this shift occurs, a single oncogenic mutation can propel the cell rapidly toward malignancy.

Indeed, nearly all mice in the study developed liver cancer by the end of the experimental timeline, underscoring how potent this cellular reprogramming can be.

Transcription Factors as Molecular Switches

The researchers identified several transcription factors, proteins that regulate gene expression that appear to orchestrate this identity shift. These factors act as molecular switches, turning off mature hepatocyte programs while activating survival- and proliferation-associated genes.

Among the most notable findings were links to pathways already being targeted clinically. One transcriptional regulator highlighted in the study is the thyroid hormone receptor, a target of a drug recently approved for treating MASH (metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis) fibrosis. Another key enzyme identified, HMGCS2, is currently being explored in clinical trials for steatotic liver disease.

Perhaps most intriguing is the transcription factor SOX4. Normally active during fetal development and largely silent in adult liver tissue, SOX4 was found to be reactivated under high-fat stress. Its re-emergence signals a regression to developmental gene programs an echo of embryonic plasticity in an adult organ.

These discoveries suggest that pharmacologically targeting the molecular drivers of de-differentiation could help maintain hepatocyte maturity and reduce cancer risk in vulnerable populations.

From Mouse Models to Human Disease

To determine whether these findings were relevant to human disease, the researchers analyzed gene expression data from liver tissue samples taken from patients at various stages of liver disease, including individuals who had not yet developed cancer. The human data closely mirrored the patterns observed in mice.

As liver disease advanced, genes responsible for normal liver function declined, while genes associated with immature cellular states and stress adaptation increased. Importantly, these gene expression signatures were not merely descriptive, they were predictive. Patients with higher expression of pro-survival, de-differentiation-associated genes had poorer survival outcomes once tumors developed.

This suggests that transcriptional reprogramming precedes and predicts cancer aggressiveness, offering potential biomarkers for early risk stratification.

A Long Timeline in Humans

While mice developed liver cancer within roughly a year of high-fat diet exposure, the researchers estimate that in humans this process unfolds over decades, often 15 to 25 years. This extended timeline explains why liver cancer is typically diagnosed later in life, long after metabolic risk factors have been established.

Dietary habits, alcohol consumption, viral infections, and genetic susceptibility all influence how quickly this process progresses. Crucially, the long latency also represents a window of opportunity for intervention.

Can the Process Be Reversed?

One of the most important unanswered questions is whether hepatocyte de-differentiation is reversible. The MIT team now plans to investigate whether returning to a normal diet, or using weight-loss therapies such as GLP-1 receptor agonists, can restore mature liver cell identity.

If metabolic normalization can re-establish differentiation programs, it would provide strong biological justification for aggressive early intervention in fatty liver disease not merely to reduce inflammation, but to prevent cancer at its cellular roots.

Rethinking Liver Cancer Prevention

This study fundamentally shifts how liver cancer risk is understood. Rather than viewing cancer solely as a consequence of accumulated mutations, it highlights cellular identity loss as a critical enabling factor. High-fat diets do not simply increase mutation rates; they reshape the cellular landscape so that mutations become far more dangerous.

As Alex K. Shalek, senior author of the study, emphasizes, chronic stress forces cells into survival modes that come at a long-term cost. Understanding these trade-offs opens new therapeutic avenues, aimed not just at killing cancer cells, but at preserving healthy cell identity before cancer begins.

In a world where high-fat diets are increasingly common, these findings carry urgent implications. They underscore that metabolic health is not just about energy balance or cardiovascular risk, it is deeply entwined with the molecular stability of our cells. Protecting liver health may ultimately mean protecting cells from being pushed backward into a state where cancer becomes almost inevitable.